The crowd deaths at a Houston music festival added even more names to the long list of people who have been crushed at a major event.

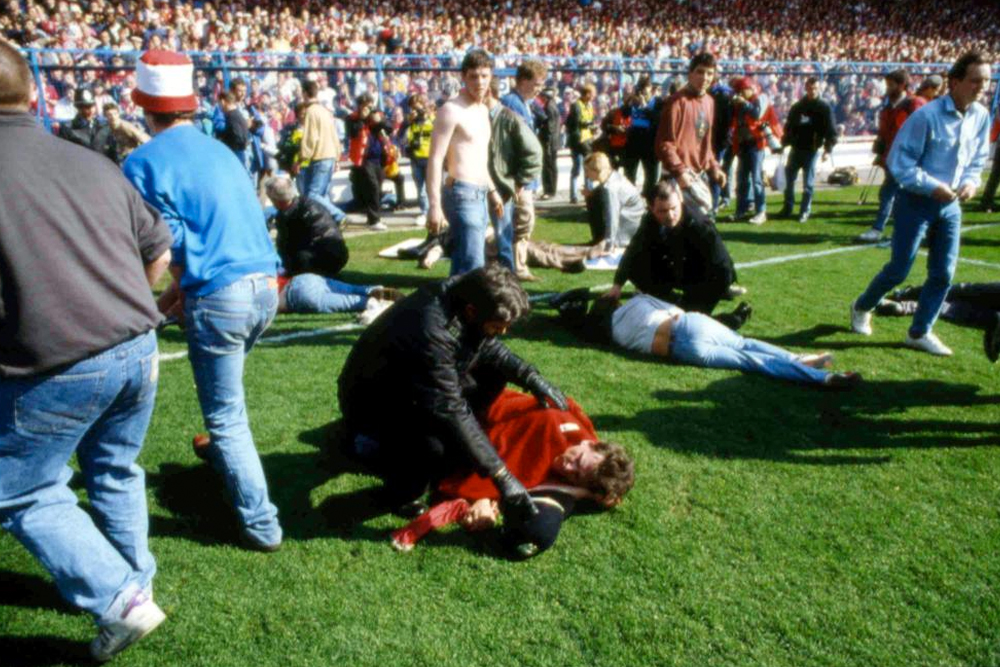

Tragedies like the one Friday night at the Astroworld Music Festival have been happening for a long time. In 1979, 11 people died in a scramble to enter a Cincinnati, Ohio, concert by The Who. At the Hillsborough soccer stadium in England, a human crush in 1989 led to nearly 100 deaths. In 2015, a collision of two crowds at the hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia caused more than 2,400 deaths, based on an Associated Press count of media reports and officials’ comments.

Now that more people are heading out of their homes and back into crowds after many months of being cooped up because of the pandemic, the risks are rising again.

Most major events happen without a death, of course, but experts say they see common traits within the tragedies. Here’s a look at how they happen:

HOW ARE PEOPLE DYING IN THESE EVENTS?

They’re often getting squeezed so hard that they can’t get any oxygen. It’s usually not because they’re getting trampled.

When a crowd surges, the force can be strong enough to bend steel. It can also hit people from two directions: one from the rear of the crowd pushing forward and another from the front of the crowd trying to escape. If some people have fallen, causing a pileup, pressure can even come from above. Caught in the middle are people’s lungs.

WHAT’S IT LIKE TO BE SWEPT IN?

A U.K. inquiry into the Hillsborough tragedy found that a form of asphyxiation was listed as an underlying cause in the vast majority of the deaths. Other listed causes included “inhalation of stomach contents.”

The deaths occurred as more than 50,000 fans streamed into the stadium for a soccer match on a warm, sunny day. Some of them packed into a tunnel and were getting pressed so hard into perimeter fencing that their faces got distorted by the mesh, the inquiry found.

“Survivors described being gradually compressed, unable to move, their heads ‘locked between arms and shoulders ... faces gasping in panic,’” the report said. “They were aware that people were dying and they were helpless to save themselves.”

WHAT CAUSES SUCH EVENTS?

“My research covers over 100 years of disasters, and invariably they all come down to very similar characteristics,” said G. Keith Still, a visiting professor of crowd science at the University of Suffolk in England who has testified as an expert witness in court cases involving crowds.

First is the design of the event, including making sure that the density of the crowd doesn’t exceed guidelines set by the National Fire Protection Association and others. That includes having enough space for everyone and large enough gaps for people to move about.

Some venues will take precautions when they know a particularly high-energy crowd is coming to an event. Still pointed to how some will set up pens around stages in order to break large crowds into smaller groups. That can also allow for pathways for security officers or for emergency exits.

WHAT ARE OTHER CAUSES?

The crowd’s density may be the most important factor in a deadly surge, but it usually needs a catalyst to get everyone rushing in the same direction.

A sudden downpour of rain or hail could send everyone running for cover, as was the case when 93 soccer fans in Nepal were killed while surging toward locked stadium exits in 1988. Or, in an example that Still said is much more common in the United States than other countries, someone yells, “He has a gun!”

Surges don’t always happen because people are running away from something. Sometimes they’re caused by a crowd moving toward something, such as a performer on the stage, before they hit a barrier.

Still also cited poor crowd-management systems, where event organizers don’t have strong procedures in place to report red flags or warnings, among the reasons deadly surges happen.

HOW HAS THE PANDEMIC AFFECTED THINGS?

Steve Allen of Crowd Safety, a U.K.-based consultancy engaged in major events around the world, said it’s always important to monitor the crowd, but especially so now that events are ramping up in size following the the pandemic lockdown.

“As soon as you add people into the mix, there will always be a risk,” he said of crowds.

He recommends that events have trained crowd spotters with noise-cancelling headsets who are in direct communication with someone in close proximity to the performer who’s willing to temporarily stop the event if there’s a life-threatening situation. That could be a crowd surge, structural collapse, fire or something else.

Allen said he has personally stopped about 25 performances by the likes of Oasis, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Eminem.

WHY AREN’T PEOPLE CALLING THIS A STAMPEDE?

Professionals don’t use the words “stampede” or “panic” to describe such scenarios because that can put the blame for the deaths on the people in the crowd. Instead, they more often point at the event’s organizers for failing to provide a safe environment.

“Safety has no profit,” Still said, “so it tends to be the last thing in the budget.”