The hissing of a water hose spraying the ground reverberates around the walls of the dimly lit Empire Cinema in Lebanon’s northern city of Tripoli. From the floor of a paint-chipped room that was once a ticket office, a man sorts through rusty bolts and screws, while in the adjacent foyer, a woman sweeps dust off a mirror. The person leading the restoration efforts is 35-year-old actor and director Kassem Istanbouli, known for his theater work throughout Lebanon.

Several days a week, his team — which includes a Syrian, a Palestinian, a Lebanese and a Bangladeshi — drives three hours from their homes in the country’s south to work on the space, built in the early 1940s but abandoned for decades. The restoration project launched last month is the first of its kind in hardscrabble Tripoli, Lebanon’s second largest city more often known in recent years for sectarian and other violence.

“What we are trying to say is that Tripoli is a city of culture and art,” Istanbouli said. “When you open a cinema and a theater, people will come and attend. But if you give them a gun, of course they will shoot at each other and kill each other,” he added. For much of the rest of Lebanon, Tripoli’s artistic history is considered a relic of the past, overshadowed by crushing poverty, corruption, and migration. But Tripoli has an especially long cinematic tradition, once boasting up to 35 movie houses, including Lebanon’s first.

Cinema Empire is the last of five historic cinemas still standing in Tripoli’s Tell Square, which encircles a clock tower gifted by Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II in the early 20th century. It shut down in 1988 as massive cinema complexes opened inside malls, and home video players grew in popularity. Istanbouli, founder of the Tiro Association for Arts in the southern city of Tyre, has already transformed three abandoned cinemas there into theater and film venues.

Much like Tyre’s Rivoli theatre which he restored in early 2018, Istanbouli aims to transform the Empire into a multi-purpose venue featuring not only arts festivals and plays, but also a library, a visual arts studio and area for workshops. That’s no small order these days, given a crippled economy and over 80% of the population living in poverty.

Even before a financial crisis led to the current depression, Tripoli was already Lebanon’s poorest city — plagued by government neglect and a lack of investment. It has been a major point of departure for illegal migration, with Lebanese now following the same precarious path as Syrians fleeing their civil war, trying to reach Europe via the Mediterranean.

The director’s project was inspired by his father, an electrician who used to repair movie houses in the south, and his grandfather, who was a sailor and hakawati — a storyteller who sported a red fez while recounting folkloric tales in Tyre’s old cafes. “This project will improve the city economically. It will bring tourism and change to its reputation,” Istanbouli said.

Charles Hayek, a 39-year-old historian and conservationist said that Istanbouli’s project will do more than just fight negative perceptions. “Kassem is saving one of the heritage buildings and giving it back life,” he said.

Tripoli has lost much of its architectural heritage — especially around Tell Square — in the past decade due to neglect. Before the 1975-1990 civil war, the square’s oldest cinema, Inja, once attracted two of the Arab world’s biggest music celebrities: Umm Kalthoum and Mohamed Abdel Wahab. That building has now been demolished, replaced by a parking garage.

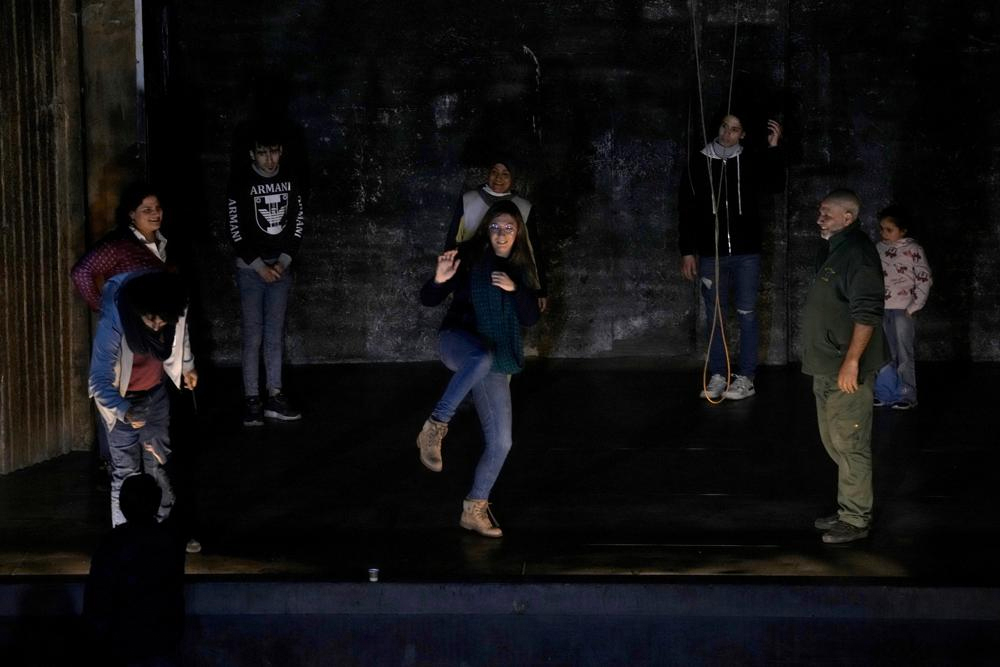

For rehabilitation funds, Istanbouli has partnered with the DOEN Foundation and The Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders. The cinema contract from a private owner is for five years, and he hopes to officially open within six months. One afternoon, Istanbouli led volunteers who had finished with repairs through acting exercises.

“Pretend that you’re an animal,” he said to a woman who then announced she was a panda. “Now I want you to face off against a dog… who wants to be a dog?” he asked.

Maha Amin, one of the attendees from Tyre who was sweeping dust off mirrors in the morning and was now on stage, never thought about the possibility of acting, let alone visiting Tripoli.

“The environment we live in doesn’t accept a woman who is my age to do this,” the 57-year-old special needs teacher said. She initially went to Istanbouli’s Rivoli theater in Tyre to enroll her seven grandchildren, but ended up joining them.

“Especially in the tough times today, people need to breathe and express themselves,” she said. “It’s here on stage after a long day of work that I’m able I’m able to say what I want, in total freedom.”