The historic London residence of Lord Frederic Leighton reopened on Saturday after undergoing a comprehensive renovation that provides a window into the opulent, meticulously preserved world of Victorian artists.

And now, after 18 years of painstaking conservation and restoration work, which cost £8 million (US$8.88 million), it is once more basking in its former splendor.

A year-long exhibition program will be exhibited across two new gallery spaces which was renovated by the architecture firm BDP.

The history of this opulent location begins with Lord Frederic Leighton, one of the most notable artists and travelers of the Victorian era, who was only in his mid-thirties when he began construction on his red-brick home and studio in the Holland Park area in 1864.

The architect George Aitchison designed the two-story townhouse. The elegant home was a work-in-progress for more than 30 years, up to Leighton's death in 1896. It had a library, a dining room, a grand staircase, a blue "Narcissus Hall," and a glass enclosed studio bathed in natural light. Leighton's plain bedroom, having a single bed, was the only private area in the house.

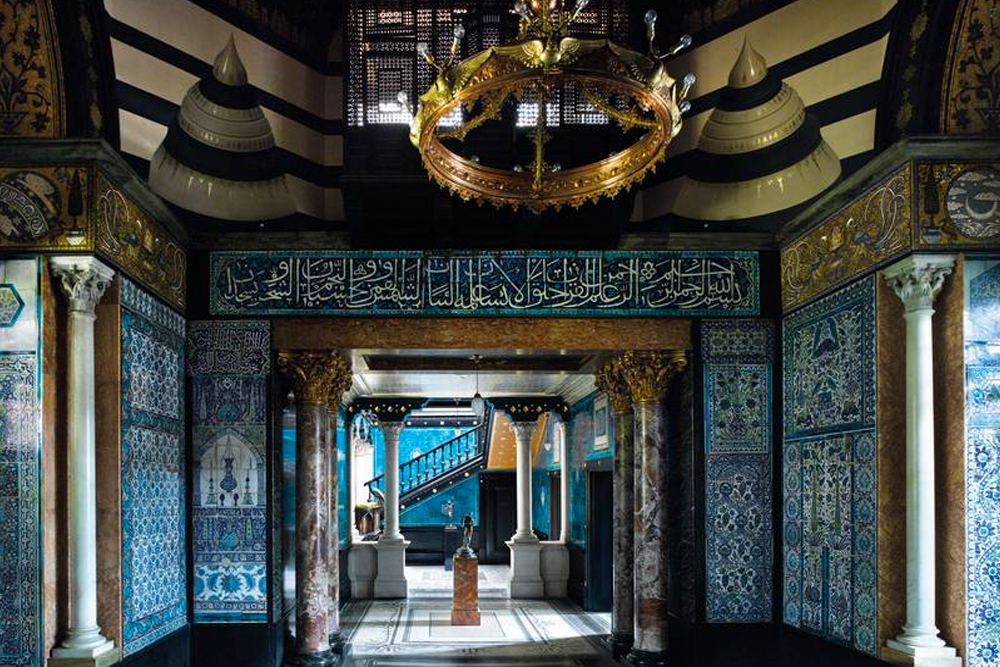

The Arab Hall declared to be the highlight of Leighton's home was built in 1877 and was modeled after the historic Arab-Norman palace "La Zisa" (or "Al-Aziza" in Arabic) in Palermo, Sicily. Its golden mosaics, honeycomb wall recesses, and fountains captured the attention of both Leighton and Aitchison.

Leighton's Arab Hall was transformed into a cozy oasis with the addition of Iznik tiles that the well-traveled artist purchased in Syria, Egypt, and Turkey, as well as a glittering mosaic frieze with images of mythological creatures, deer, birds, flowers, vines, and more, which is topped by a grand golden dome. The aesthetically spectacular tiles are set up as a secluded inner courtyard.

A water feature cools the area and provides seating in the corners. Leighton's fantasy of life in the Ottoman Empire, a prime example of British Orientalism, is viewed above from a little mashrabiya. The tiles' Arabic calligraphy, which includes Qur'anic texts, is an essential component. Even though the order of some of them has been swapped, disrupting the flow. “His response to the material was absolutely an aesthetic one rather than a scientific one,” according to Daniel Robbins, senior curator at Leighton House.

Syrian artisans from Turquoise Mountain, an NGO, were employed to salvage and recreate objects, and a mural by Iranian-Canadian artist Shahrzad Ghaffari was commissioned. Rumi, a poet from the 13th century, served as inspiration for the mural, and the lettering's intense blue color alludes to the turquoise tiles in Narcissus Hall.

“The message of the mural is very important,” says Ghaffari. “It’s about bringing East and West together”. “And I hope that this message goes to future generations that will embrace different cultures: the message of unity.”